Fifth Sunday of Lent

EZ 37:12-14 PS 130:1-8. ROM 8:8-11 JN 11:1-45

As we continue to hunker down in our quarantine, it is becoming increasingly difficult to focus on any task, be it work or personal, without lapsing into a pensive, even melancholy mood. Instigated by news and newsfeeds alike.

Earlier this week the internet responded ambivalently to celebrities’ attempts at giving hope to the masses from the comfort and safety of their own self-isolation. In a viral Instagram post, Gal Gadot, the ringleader, singing along with other celebrities to John Lennon’s “Imagine”, invites the public to imagine a world with “no need for greed or hunger”. The irony of this feat does not go unnoticed. The, probably well-intentioned, attempt at demonstrating solidarity is prefaced by Gadot saying that these days had her feeling a bit philosophical. We plebeians too can relate to the feeling.

America Magazine recently published an article about Editor Matt Malone’s self-quarantine wherein he consults the philosopher Albert Camus, specifically his novel The Plague. A novel which is experiencing a surge in sales given our global state of existential angst. Malone’s instinct is spot-on. What better time than this, living through a global pandemic, to dust off the tomes of the existential philosophers.

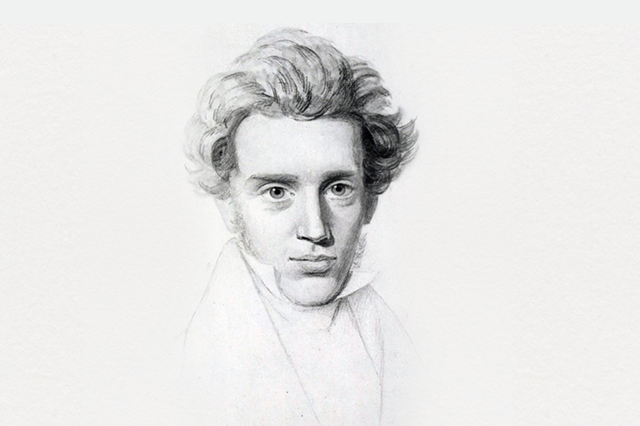

In that vein I find this moment opportune for a philosophical excursion that goes just a little further back to a Danish philosopher, widely considered the father of existentialism, Soren Kierkegaard. Fortuitously, one of Kierkegaard’s great works, The Sickness Unto Death, takes today’s Gospel reading as its starting point. This book forms a part of the pseudonymous literature composed by Kierkegaard. Thus, it is written under the pseudonym Anti-Climacus, though not his own voice, he regards it as upbuilding and demanding, even exceedingly so, in its perspective.

The passage in today’s Gospel is from the eleventh chapter of John. The text relates the story of the raising of Lazarus from the dead. In it, Martha and Mary send word to Jesus that “the one you love is ill.” (Jn 11:3) We know that Lazarus is a close friend of Jesus because of the tears shed in what is well known as the shortest verse in the Bible, “Jesus wept.” (King James translation Jn 11:35)

Jesus’ response, in the King James and Douay-Rheims archaic language, is “This sickness is not unto death, but for the glory of God…” (Jn 11:4) Lazarus did die though, Kierkegaard reminds us. When Jesus says Lazarus is asleep, the disciples misunderstand him, requiring Jesus to be utterly clear, “Lazarus has died.” (Jn 11:14) Some exegetes understand the text to mean that this event would not end, finally in Lazarus’ death, but in his being raised from the dead.

Kierkegaard, however, notes an incongruence here. Either this sickness kills Lazarus, or it does not; it does, according to the gospel. Thus Jesus, knowing Lazarus would die, could not have indicated to his disciples at one moment, don’t worry this will not kill him, then at another that though it killed him he will be raised. Therefore, the sickness of Lazarus was one which would lead to his death, but it was not the sickness unto death.

Even if Jesus did not raise Lazarus, Kierkegaard maintains, this sickness would not be the sickness unto death. He writes, “Humanly speaking, death is the last of all, and humanly speaking there is hope only as long as there is life. Christianly understood, however, death is by no means the last of all…” (SU, 7) Kierkegaard’s contribution here is valuable, not so much for his biblical exegesis, but for his keen philosophical insight into this fate worse than death, the sickness unto death. Despair is the sickness unto death and Kierkegaard astutely diagnoses this as a sickness of the spirit.

Like a skilled surgeon with a razor-sharp scalpel, Kierkegaard the spiritual physician plumbs the depths of the psyche, dissects and exposes the ins and outs of this spiritual sickness. The book is a veritable typology of despair. I would draw your attention now to just a few of the most provocative lines from this work which cut to the chase.

Despair can be so deep that no one detects it, he writes, but deeper still,

“…it can be so hidden in a man that he himself is not aware of it! And when the hourglass has run out… when the noise of secular life has grown silent and its restless or ineffectual activism has come to an end, when everything around you is still, as it is in eternity, then… eternity asks you one thing… whether you have carried this sickness inside of you as your gnawing secret, as a fruit of sinful love under your heart, or in such a way that you, a terror to others, raged in despair.” (SU, 27)

In our newfound lingua franca, epidemiology, it’s easy to understand how a person infected with a virus, can walk around asymptomatic, and worse can infect others, so too the despairing person can walk about “without ever becoming conscious of being destined as spirit…” (SU, 26) Despair noxiously permeates even the lovely, the pleasant, “deep, deep within the most secret hiding place of happiness there dwells also anxiety, which is despair; it very much wishes to be allowed to remain there, because for despair the most cherished and desirable place to live is in the heart of happiness.” (SU, 25) But currently, we are not in those still waters of jovial times. Now it seems to bubble up at every turn.

We are living a moment which threatens to turn us all into philosophers. We cannot help but to dwell on the ethical dimensions of our activities, down to the slightest tasks. When grocery shopping, taking more than one’s allotment becomes an ethical dilemma. Worse, touching an infected surface makes me, potentially, death’s harbinger. It is enough to make anyone despair.

There is only one light I know which remains when all others grow dim. Ultimately, Kierkegaard prescribes a cure for this sickness. That is, the self’s proper relation to itself in all of its dialectical tensions, between necessity and possibility, freedom and determinism, finitude and infinitude, psychical and physical. Ultimately the self must rest “transparently in the power that established it.” (SU, 131) Faith.

In this fifth week of Lent, we have arrived at the climactic point in Jesus’ teaching leading us into Holy Week. In the celebration of our Easter liturgies commemorating Jesus’ life, death and resurrection, he no longer teaches us about the paschal mystery, but invites us to enter into it. Through the readings in these past weeks Jesus has demonstrated the power of God to heal the brokenness of the world. Jesus has allowed us to see, at least partly, the glory of God. Now, in raising Lazarus, the last of the seven signs in the Gospel of John, he demonstrates that even that final evil, death, can be conquered.

On Friday of the fourth week of Lent the Catholic faithful experienced a historical event, an extraordinary Urbi et Orbi in which the Pope invited the whole world to pray with him for an end to the coronavirus pandemic. He exposed the Blessed Sacrament for adoration and imparted his Apostolic Blessing, offering everyone the opportunity to receive a plenary indulgence.

In his reflection, he describes a what is felt around the world at this moment, “Thick darkness has gathered over our squares, our streets and our cities; it has taken over our lives, filling everything with a deafening silence and a distressing void, that stops everything as it passes by; we feel it in the air, we notice it in people’s gestures, their glances give them away.” Something not unlike the despair described by Kierkegaard.

Like Kierkegaard who prescribes faith as the cure for despair, Pope Francis notes how ordinary people are animated by faith to exercise patience daily, taking care not to sow panic but shared responsibility. Parents and grandparents lifting their gaze up, showing their children how to navigate a crisis, adjusting their routines. Pope Francis reminds us of Jesus’ words, “Why are you afraid? Have you no faith”? Faith begins when we realize we are in need of salvation. We are not self-sufficient; by ourselves we flounder: we need the Lord, like ancient navigators needed the stars.”

Image credit – source of original image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:S%C3%B8ren_Kierkegaard_(1813-1855)_-_(cropped).jpg